Vintage Vermont Lore III: The Brimmer Massacre on Indian Massacre Road

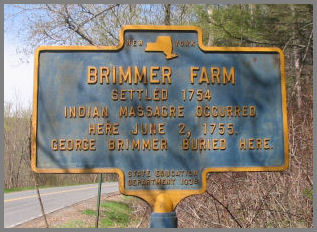

When I first moved to the area about two and a half years ago, I took it upon myself to get more acquainted with the area. Needless to say I got in my car and drove around for a couple of hours. Anyone who has been to Pownal probably understands that this was not the most interesting trip in the world; all there is to see are farms, farms, and more farms. The back roads offered a view of a forest filled with tall, lean trees, concealing very little mystery in the southern Vermont woods. Convinced that I had moved to the most boring place in Vermont, a difficult title to win no doubt, I turned my car around and started heading back towards North Pownal. It was then that I noticed a sign peeking out of the trees. Crooked on its post, it marked a dirt road parallel to an old cemetary right off Route 346, as “Indian Massacre”.

As one may expect, I was quite put off by the name, not only because of its less than politically correct connotation, but by what it implied happened there. My mind was swimming with questions as all at once Pownal became the most interesting place in the world to me. I had to know what happened.

The story behind the name goes back to the French and Indian War, when the state of Vermont didn’t exist, and this whole area was part of New York. In June of 1754, farmers in the area were in their fields, checking on their summer crops. Johannes George Brimmer was not any different. He and his three sons, Jeremiah, Johnathan, and Godfrey, were out in their cornfield in the early morning hours of June 15th. They patrolled the planted rows, as farmers so often do, as anything amiss could easily threaten their entire crop. It was then, as the story goes, that Johannes noticed something lying on the ground, between the mounds. Moving closer, he looked down at the object, realizing it was a blanket, and took note of the pattern on the intricately woven fabric. This wasn’t just a simple blanket; it was a Mohican blanket, lying in his fields, almost mockingly. If it was meant to catch his attention it had succeeded.

One can only imagine the panic that must have seized the farmer as he stood and sought out his sons, in fear of the unseen enemy lurking at the border of his fields. The young men were quick to grasp their father’s concern, quickly calling out to their horses in an attempt to make it back to the farmhouse on the far end of the corn field. Jeremiah had just swung his leg over the saddle when the sound of a rifle broke the tense morning silence. According to the Hoosick Historical Society’s records, the leaden bullet tore through the Brimmer boy’s chest. He fell from his saddle, dead as his brothers struggled with their own weapons to defend themselves against the onslaught pouring out from the tree line. Johannes managed to get on his horse, in an attempt to get back to the house and retrieve his other sons, while Johnathan and Godfrey exchanged gunfire with the tribal warriors.

Whether they realized that they were painfully outnumbered, or were just too frightened by the sight of their brother, exsanguinating before their very eyes, we do not know. What the records do tell us is that the boys dropped their muskets, fell to their knees, and placed their left hands on the butt, a sign of surrender. The Mohicans ceased fire, falling upon the boys with whoops and what could only be seen as cries of victory, as they confiscated their guns and tied them up before marching the two younger Brimmers away from their family farm. It would be nearly a decade before they would see their home again.

From there they were taken back to the Native American camp, where they were made to join in on their festivities, chanting and dancing around the fire in celebration of the victory won against the English citizens. The Mohicans lauded the boys’ attempts to resist, but in the end it was futile. Johnathan and Godfrey were their prisoners and they would not know freedom again for a very long time.

Over the next few weeks the Mohicans marched them from Petersburg New York, up to St. John’s Canada, where they faced execution. As they stood on the executioner’s block, resigned to their fate, a Native American elder spoke up from the crowd, saving their lives as he recounted how they and the Brimmer family had helped him when he had traveled through Hoosick only a few months before. With this revelation their lives were spared, but they were not to be freed; instead the Mohicans sold the Brimmers to the French Army only a few weeks later.

For five years Johnathan and Godfrey served French officers as slaves, the very course of their lives changed by that one fateful morning. If it was not for the war, they very well may have died that way as well. However, on September 13, 1759 the battle broke out between the British Navy and the French occupying Quebec right outside of the city walls. This pivotal battle would see the fall of the city to the English, and prove to be a deciding moment in the Seven Year’s War, but for the Brimmer boys it proved to be something quite different; an opportunity, and not one that they would let go to waste.

Seizing the chance, they made their escape down through New York, fleeing back to the colonies through New York. It was near Fort Ticonderoga that their luck ran out as they were once again captured, this time by the British, who hauled the young men into custody, where they once again faced the possibility of death right when freedom seemed to be so close at hand. Fortunately for the Brimmers, fate was smiling kindly on them, sending a messenger in the form of Patroon Stephen Van Rensselaer, who reportedly was familiar with the Brimmer case. He wasted no time pardoning the boys, securing not only their release, but also their return to their farm on the Vermont New York border, thus ending their long and harrowing tale.

The Brimmers stayed on for nearly two hundred more years, when in 1933 they finally sold the family farm and moved from the area. Their story may have been forgotten if not for the, perhaps misleading, dirt path now known as Indian Massacre Road.

Cover photo belongs to Hoosick Township Historical Society

Melissa O’Rourke • Apr 10, 2019 at 8:43 pm

Glad you found my family history interesting, though some of the details aren’t entirely accurate.

My Grandmother was a Brimmer. My Mother wrote about her many happy memories spent on the Brimmer farm.

It was still owned by the Brimmer’s later than 1933., but I’m not sure of the exact date it was sold. My Great Grandfather, Byron was concerned about the tragedies that occurred there.

Trust me, their story won’t be forgotten and we’ve recorded it for generations to come!

Thank you!

Greg Wibterhalter • Mar 12, 2019 at 9:02 am

I have been a Pownal resident for about 28 of my 49 years in the Bennington area and a professor( retired) at SVC. It was great to read your article on the Indian Massacre. I have hiked through those woods many times over the years. I really liked seeing this in the Looking Glass. Thanks!